Machine Learning for Compact Binaries

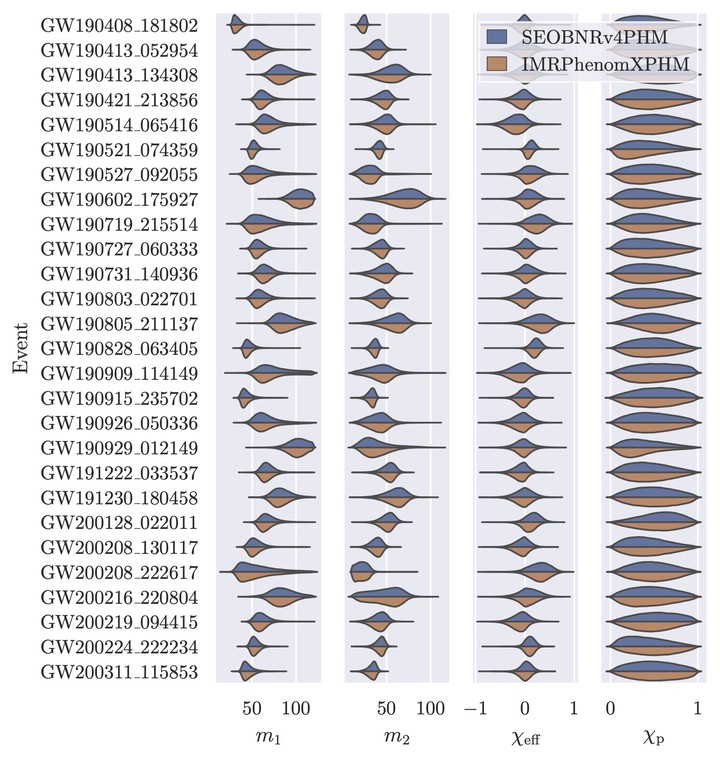

Inferred masses and effective spin parameters for events from the second and third Graviational-Wave Transient Catalogs. Results come from Dingo-IS. The two colors refer to two different waveform models.

Inferred masses and effective spin parameters for events from the second and third Graviational-Wave Transient Catalogs. Results come from Dingo-IS. The two colors refer to two different waveform models.The central goal in analyzing data from gravitational-wave detectors is to determine the properties of the source (e.g., the masses, spins, location, etc., of the binary) that could have given rise to the observed data. This is accomplished with Bayesian inference. Given a likelihood

The task of inference is to obtain samples

The goal of this research project is to train a neural network to learn an inverse model for the system parameters given the data. Once trained, this can instantly provide posterior samples for any observed data. We build a “surrogate” for the posterior using so-called

“normalizing flows”, which allow us to represent the complicated posterior distribution in terms of a mapping (depending on the data) from a much simpler distribution,

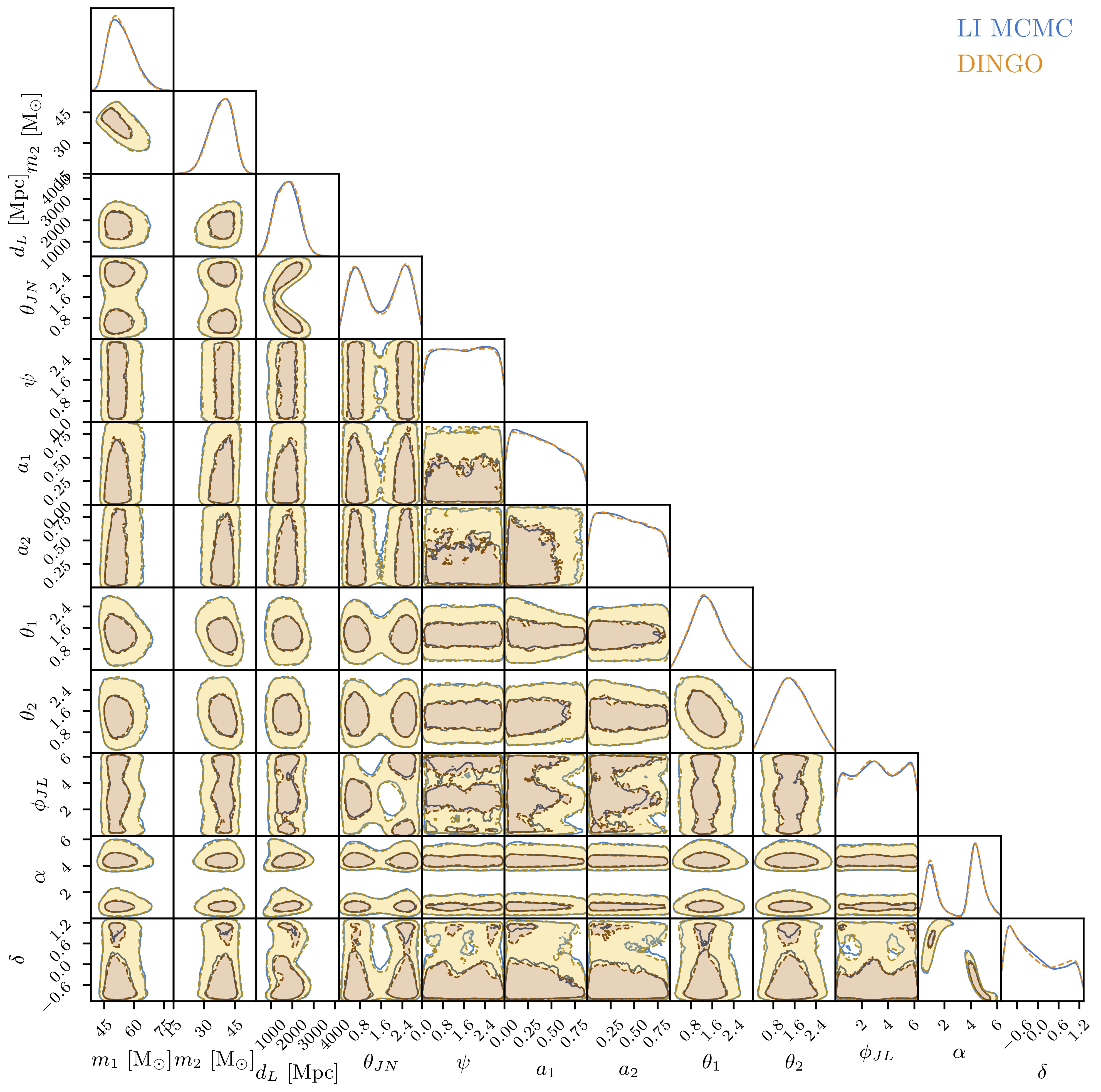

Quasicircular binary black hole systems are characterized by 15 parameters, and our networks are able to infer all of them simultaneously, with results in very close agreement with standard analysis codes. Additionally, treating these samples as a proposal for importance sampling, we can verify the deep-learning results, correct them if necessary, and obtain an extremely precise evidence estimate.

We are currently working on building a user-friendly code, called “Dingo”, which we plan to make publicly available. Beyond that the next steps are to

Use the code to analyze more real events with the most realistic waveform models, as well as to search for deviations from Einstein’s theory of gravity.

Extend to binary neutron stars, which have much longer waveforms. This is especially important for rapid alerts to standard telescopes, since these events are much more likely to have multimessenger counterpart signals.

Include a treatment of more realistic (nonstationary or non-Gaussian) noise. This is challenging for conventional approaches, but can be done naturally using simulation-based inference methods such as ours. This will lead to more accurate inference results than otherwise possible using standard codes.